“The world is too much with us; late and soon, getting and spending, we lay waste our powers.” William Wordsworth wrote that in 1802. By “world” I assume he meant something similar to what St. John had in mind when he exhorted his readers not to love the world – a world comprised of the “lusts of the flesh, the lust of the eyes, and the pride of life.”

If Wordsworth thought the world was intrusive at the turn of the 19th century, what would he (or St. John) say now in this time of continuous advertisements, outsized corporate ambitions, and persuasive social media influencers? It impinges on us every waking hour. It screams for our attention and, if we ignore it even for a moment, warns us of the danger of missing out.

It is not only the social world that presses on us. The physical world does too, all day, every day. One can think of human beings – empiricists do it all the time – as astonishingly complex sensors, recording inputs through touch, hearing, taste, sight, and smell. Additionally, the entire human body – and not just its sense organs – maintains a nearly constant sense of where it is in relation to its surroundings. This is the sixth sense, known as proprioception. To be human is to process millions of data points daily through our sensory inputs.

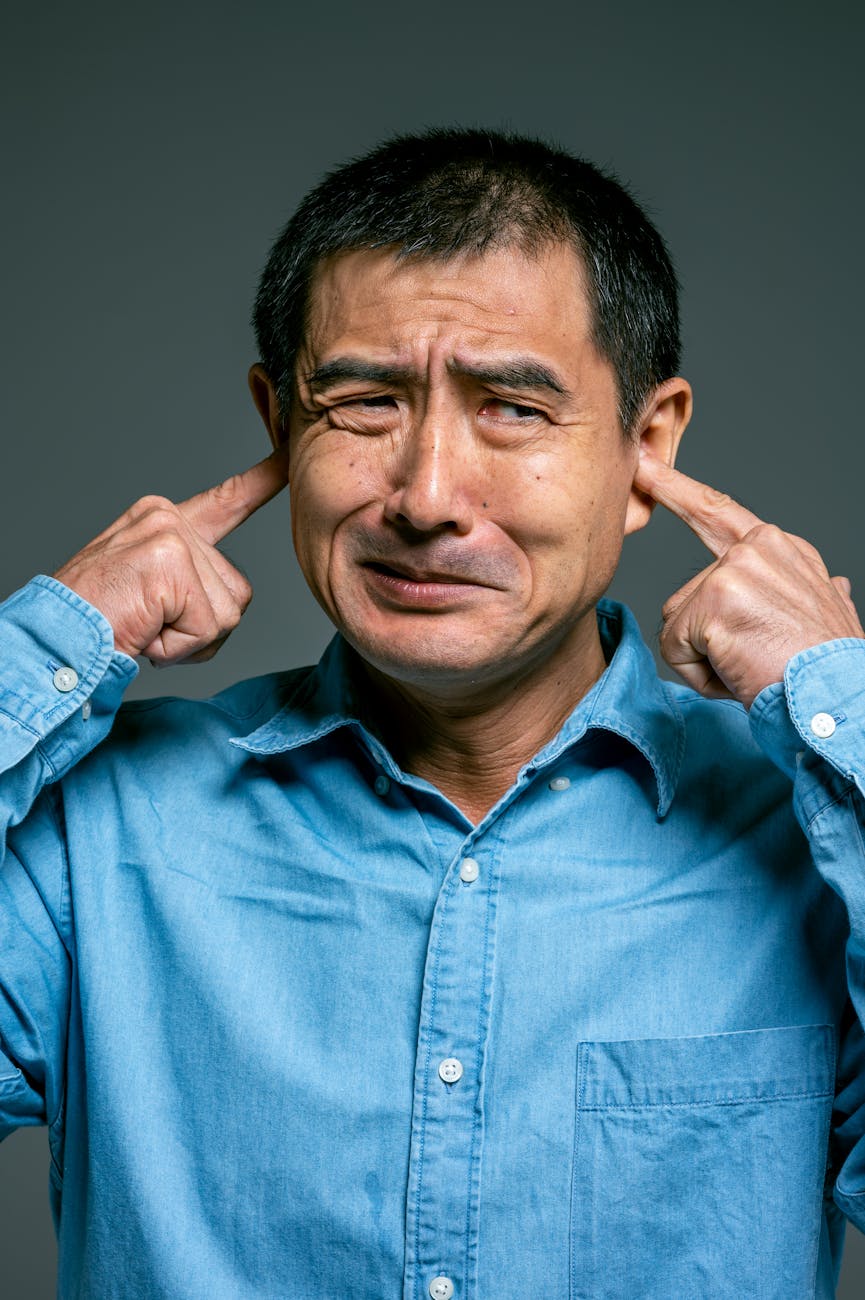

So, how can we, being human, have any attention left over for spiritual pursuits? How can we hear God speak in “a still, small voice” when our ears are being assaulted by the washing machine, the baby’s cries, and the incessant dinging of text alerts?

After writing a book on hearing God and developing a conversational relationship with him, Dallas Willard said in the epilogue, “I am still painfully aware of the one great barrier that might hinder some people’s efforts to make such a life their own. That barrier is what Henry Churchill King many years ago called ‘the seeming unreality of the spiritual life.’ We could equally well speak of it as ‘the overwhelming presence of the visible world.’”

Willard goes on to say that the “visible world daily bludgeons us with its things and events… Few people arise in the morning as hungry for God as they are for cornflakes or toast and eggs.” The visible world “bludgeons us,” while the spiritual world “whispers at us ever so gently.”

The terms “visible world” and “spiritual world” are not strictly biblical, but the idea is close to what St. Paul had in mind when he said, “…we fix our eyes not on what is seen, but on what is unseen,” and then, a few paragraphs later, adds, “We walk by faith, not by sight.”

The conflict between faith and sight is one of resource sharing. When my computer’s direct memory access controller competes with the express root port for the same memory address, something is going to lose out. Something similar happens when my ability to hear God’s voice and my addiction to the Legion voice of media compete for my limited attention: one will lose out.

Most of our resources are gobbled up by the visible, noisy world. It is simply more demanding than the spiritual world. It “is too much with us” for us to ignore it—Goliath to the spiritual world’s David.

Then why, if God wants us to be spiritual, does he allow this confounded inequality? But this question is misleading. It is not that God wants us to be spiritual; we already are. He wants us to “walk by the Spirit,” and that will not happen because the spiritual world becomes more intrusive but because we have made the choice to trust him and to listen for his “still, small voice.”

As Willard reminds us, “[N]either God nor the human mind and heart are visible. It is so with all truly personal reality. ‘No one has ever seen the Father,’ Jesus reminds us. And while you know more about your own mind and heart than you could ever say, little to none of it was learned through sensory perception. God and the self accordingly meet in the invisible world because they are invisible by nature.”

But meeting in the invisible world remains a choice, a choice based on faith: confidence that God is there and wants to meet with us. Another way of saying that is, “that he exists and that he rewards those who earnestly seek him.”

I think Wordsworth was wrong. The world is not too much with us. We are too much with the world, and that will only change if we choose it.