I recently read John 4 again. It is an altogether delightful story! Without offering any description of her features, John manages to bring the Samaritan woman to life for his readers. She is intelligent, quick-witted, tough, assertive, yet somehow vulnerable. But perhaps you don’t remember the story very well, so let me summarize it.

Jesus had been in Judea but decided to return to his home base in Galilee (in the north). For some reason, “he had to go through Samaria.” A traveler from Judea to Galilee could cut many miles off the trip by cutting through Samaria, but Jewish people frequently took the longer route to avoid contact with the despised Samaritans. (More about this below.) But for some reason, Jesus “must needs” (KJV) go through Samaria.

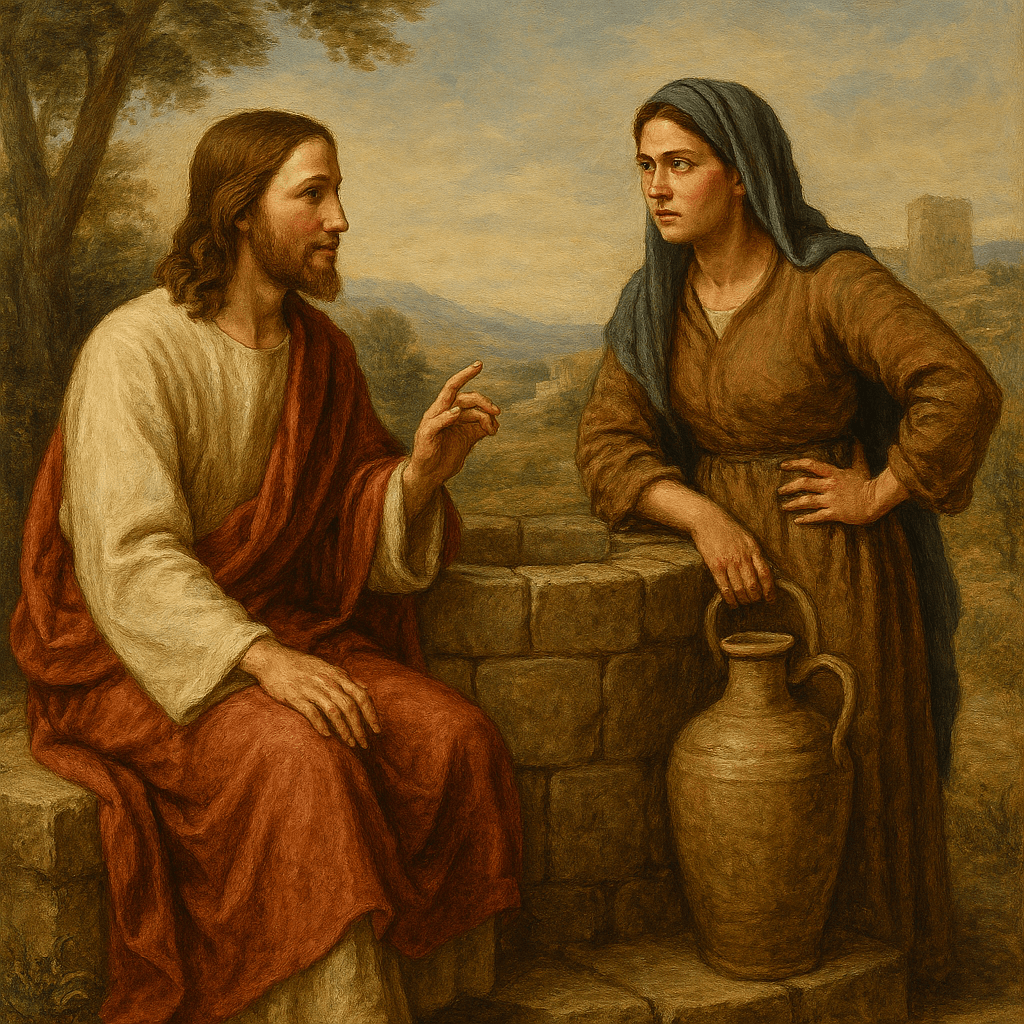

He and his disciples arrived outside the village of Sychar and stopped at an ancient well that was purportedly dug by the patriarch Jacob. Jesus waited there while his disciples went into the village to buy food. While they were gone, a woman from the village came to fill her water jars, and Jesus engaged her in conversation—to her great surprise.

Any other Jewish teacher – pretty much any other Jewish person – would have sat quietly or even removed himself from her neighborhood. Jews felt a hearty dislike of Samaritans and vice-versa. But Jesus didn’t merely engage the woman in conversation. He didn’t say, “A mighty hot streak of weather we’ve been having.”

When the woman saw him, she would have realized that he was a Jew. As she lowered her container into the well, she would have kept an eye on him. You can’t trust a Jew, she would be thinking.

How surprised she was when he spoke to her. And she was even more surprised by what he said. The NIV softens his words to make them more polite: “Will you give me a drink?” In Greek, it does not sound nearly so nice: “Give me a drink!”

The woman came right back with a question: “You are a Jew and I am a Samaritan woman. How can you ask me for a drink?” Jews did not associate with Samaritans. They would not eat with them and, heaven forbid (and they were sure heaven had) that they should use a cup or plate or spoon that a Samaritan had previously used. Samaritans were unclean. They had cooties, as the boys said when I was in elementary school. And if you drank from a Samaritan cup, you’d have them too.

The back and forth in the conversation that follows is lively and realistic. When Jesus broaches the subject of the woman’s family situation (he tells her to get her husband and come back), the woman nimbly changes the subject by raising an ecclesial point of contention between Jews and Samaritans. It appears that she was trying to lead Jesus off into the tall weeds of theological controversy, where she might just lose him.

But Jesus never gets lost. He volleyed back the woman’s words with a profound truth about the nature of God and the nature of authentic worship. She pivots once more with what was meant to be a conversation-ending statement: “When Messiah comes, he’ll explain everything.”

That’s when Jesus did something totally unexpected. He told this Samaritan that he was the Messiah. It is astounding. He had not even told his disciples this. The first person to whom Jesus revealed his messianic identity was not just a Samaritan, but a Samaritan woman. Some rabbis considered it disgraceful even to speak to a Jewish woman in public, but Jesus told this Samaritan woman who he really was.

It was then that the disciples returned and were startled to find Jesus talking with a Samaritan woman. The woman, suddenly surrounded by Jewish men, left immediately for the village. But she was not gone long, and when she came back, she brought a crowd of Samaritan men. She had told them about Jesus, wondered aloud if he really could be the Messiah, and talked them into going to the well with her. Once they met Jesus for themselves, they believed in him.

All of this is extraordinary enough, but what happened next blew the apostles’ minds. The Samaritans invited Jesus to stay with them, and Jesus accepted for himself and for his disciples. They preceded to spend the next two days in a Samaritan village. They ate Samaritan food off Samaritan plates, using Samaritan utensils—spoons that had once been in Samaritan mouths were now in theirs!

We need to understand that as good Jewish boys, the apostles were raised to despise Samaritans. If their parents knew that little Jimmy and Johnny were sleeping on Samaritan bedrolls, eating at Samaritan tables, and drinking from Samaritan cups, they would have a stroke. When the disciples heard the Samaritans’ invitation, they would have assumed that Jesus would decline. They must nearly have fainted when he accepted!

Hadn’t the Samaritans sent terrorists to desecrate the Jewish temple and defile it at Passover? (To be fair, the Jewish ruler had previously sent armed forces to destroy the Samaritan temple on Mt. Gerizim, but that story was not repeated around Jewish dinner tables.) Hatred between first century Jews and Samaritans rivaled the hatred between Jews and Palestinians today. Yet here was Jesus, enjoying Samaritan hospitality and expecting his disciples to do the same.

There is so much we can learn from this story, but I am thinking today about the prejudice and suspicion of others that existed in Samaria in the first century and in Sacramento today. Had Jesus become incarnate in 21st century America instead of 1st century Israel, one wonders if he might not take his MAGA cap-wearing midwestern disciples into the home of an undocumented immigrant for a meal and a game of Dominoes, or his CSNBC-watching followers to share a meal and family devotions with a home-schooling, Trump-voting, family of ten.

What he would not do is allow his followers to hate, demean, and traduce their fellow-disciples. Not for a minute. Not for the “sake of the country.” Not for anything.

Leave a comment